Prof. Rodger A. Randle

Prof. Rodger A. Randle

Gray these days is a popular car color. Black is popular too, and white. Any color is fine as long as it doesn’t have much color in it. There are a few red cars, but they are not a happy shade of red. They are the red of the throat lozenges that you take when you’re sick.

Henry Ford, when he launched the Model T, said that you could have it painted any color you wanted as long as it was black. There were no complaints. Owning a car in those days was glory and prestige enough in itself and the color didn’t matter. Anyway, Henry Ford had the affordable car market to himself and he could make the cars in any color he wanted. As long as the price was low, people would happily buy them. Painting all the cars the same color lowered production costs, and so black is what the customer got.

High dollar cars had always come in a variety of colors, but the people who bought these cars could afford the extra expense. Having a fine car was an especially joyous thing in the early days of automobiling, and the color of your car was a mark of privilege. The 1920s and 30s were a golden era of grand automobile designs and the super rich rode in magnificent cars with sophisticated colors that celebrated their wealth.

These Pierce Arrow ads were also notable for putting life-style in the foreground and the car in the background.

As more cars were produced, and more people could afford them, competition grew. This is where color came in. People in black cars looked at the colors of the luxury cars and wanted the same thing. Even Henry Ford eventually offered cars in a variety of colors. He had to keep up with the market.

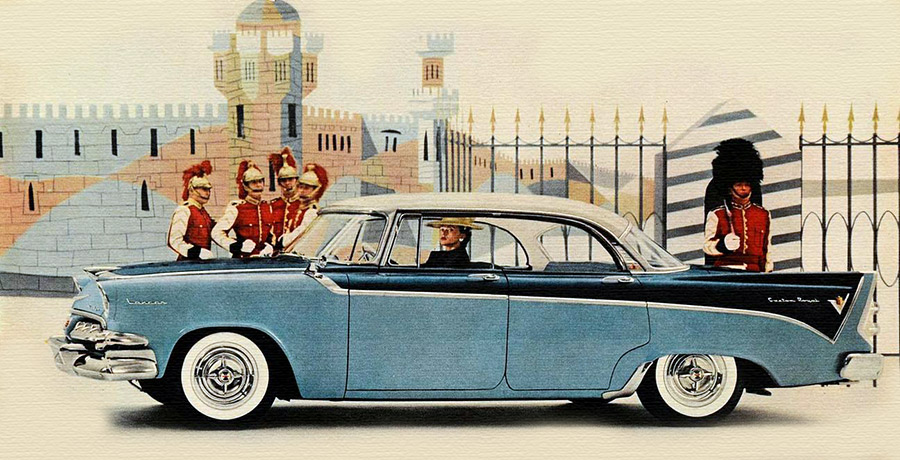

For the mass market automobile, the golden era was the 1950s. The 1949 Ford models offered a radical new design that was rounded and aerodynamic. It foretold the styling of future years. Quickly all the manufacturers followed with imaginative styling that expressed the expansive spirit of the time.

By the 1950s the depression was just a bad memory. In the post war years the incomes of Americans rose. Families began moving to suburbia where the car would play a central role in their lives. These were optimistic years of progress for many Americans, and the automobile designs from Detroit reflected this.

The 1950s began with refined good taste in car design. Cheerful colors reflected the happy consumer of the era. Increasing numbers of Americans were achieving what they considered to be the middle-class dream, and the automobile was the central expression of their new economic status.

By the end of the 1950s car styling evolved to include fins that stretched out the length of the car. Bright colors continued, but more shiny chrome was added. No matter how much Detroit exaggerated in automobile size and weight, Americans thought it was all just marvelous. It was a trend, however, that would come to a bad end in the 1970s.

Car styles followed a two-year cycle. One year styles would be introduced that were a major redesign compared to the previous year’s model, then the next year the changes were small but nevertheless identifiable. The nation's focus on the automobile meant that each year’s new model was eagerly anticipated. The unveiling of each company’s new styles was prominently covered in the newspapers, and often accompanied by splashy events sponsored by local dealers. In Tulsa, for example, I remember in the late 50´s when the local Dodge dealer erected a big tent somewhere, bigger than the dealership property could hold, to display all the versions of the new models. It attracted crowds eager to be the first to see them; new models were a source of excitement.

During these years most people could easily identify a car’s year because of the annual hoopla that accompanied the announcement of the new models. Consumer success was measured in part by the newness of your car . If your car was four or five years old your financial position did not look tiptop, and if your car was a few years old while the Joneses down the street had the latest model of the same brand, you suffered by the comparison. The Joneses were having success achieving the American Dream, but you were lagging.

The big three manufacturers each had a clear market segmentation philosophy. In the case of General Motors there were five models, each for a specific income bracket. At the top was the Cadillac for the economic elite. Next came the Buick for the near elite. Then, for those who were economically successful on a more moderate scale, there was the Oldsmobile or the Pontiac. For the mass market of middle-income Americans there was the Chevrolet. Ford and Chrysler had similar market segmentation strategies.

When this strategy of market segmentation was added to the public’s ability to spot the newness of cars by model year, it was possible precisely to measure a person’s economic status by the car they drove.

Where a person fit on this status hierarchy was important to their self-esteem, and their family’s too. It is how others judged their success. Did you look with envy at the Joneses down the street, or did the Joneses look at you with envy? Who was keeping up with whom was obvious to everyone on the block. Every time you drove down the street you announced your financial standing through the car you drove.

Pressures were powerful to conform to the status standards of the auto hierarchy. Confusion resulted when someone acted contrary to the established order. For example, a bank president would typically drive a Cadillac. Visitors and employees would see the big Cadillac parked in the space marked “Reserved for the President” and take it as a sign that the bank was prospering. If the president of the bank came to work in a three year old Ford, however, there would be confusion. People might doubt the financial solidity of the bank and start withdrawing their deposits. Confusion would extend to the employees as well. The Senior Vice President of the bank couldn’t park his new Buick in the space next to the president’s three year old Ford. It wouldn’t look right. This would extend down the line of bank officers, everyone needing to drive a car that didn’t upstage the president’s car or the car of their boss above them.

Society expected the status order of the automobile to be maintained: The president of the bank should arrive to work in a Buick or Cadillac. The senior vice president should arrive in a car with a status slightly below that. The junior vice presidents should arrive in Fords or Plymouths or Chevrolets. The custodian should arrive on a city bus. And if the chief bookkeeper for the bank arrived in a Lincoln or Cadillac or Chrysler, the auditors would be called in.

Today, of course, we still have luxury cars that proclaim the owner's status, but the days of the bright and joyful colors of the past are mostly gone. An automobile today is more of a commodity than a thing of special achievement. Everyone has one. As commodities, they might as well be colorless. The status of your car is no longer something to pridefully proclaim in attention attracting colors, not as it was in the 50's and 60's.

Prof. Rodger A. Randle

Prof. Rodger A. RandleThe top photo on this page is © Rodger Randle. The other images are details from advertisements and are no longer subject to copyright restrictions for non-commercial use.